Menu Biuletynu Informacji

The Restoration

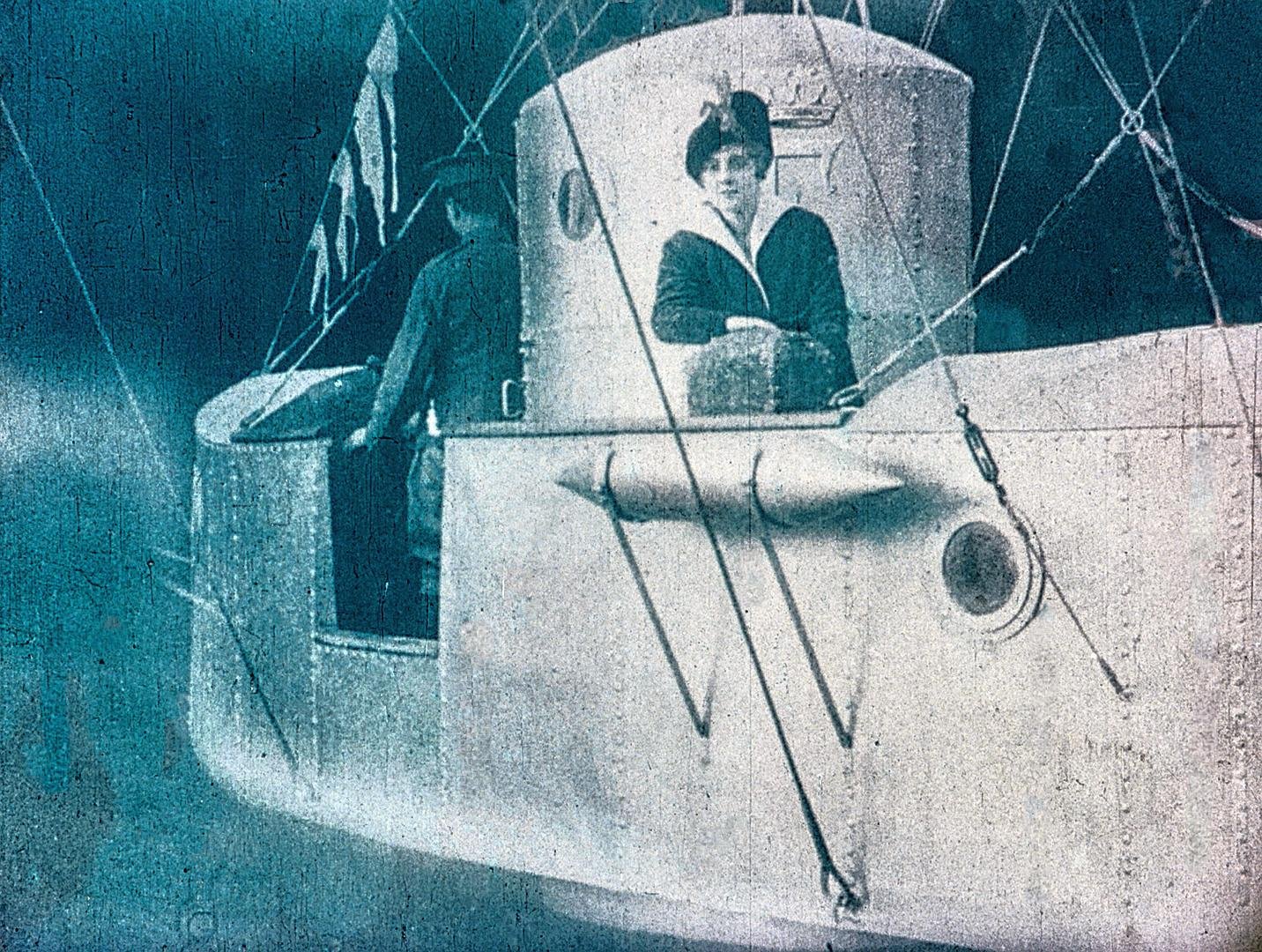

The restoration of “Filibus” has been done three times by the EYE Filmmuseum. The first time was a photochemical restoration to preserve the film from further nitrate deterioration with a new 35mm negative. It was with a new 35mm print that the Dutch intertitles were replaced by (inadequate) English intertitles. The second version was done in HD digital but the tints and tones were not correct. The third restoration carried out primarily by Annike Kross was a digitization of the internegative (the nitrate had deteriorated too much by then) that not only provided amazing depth and clarity, but taking several months, the original tinting and tone scheme was faithfully reproduced. New English intertitles, based on the Dutch version (there is no record of the Italian version) were written by Austin Renna, with a font designed by Allen Perkins, with assistance by Luyao Ma. David Emery, Marcello Seregni, Letizia Gatti, Ivo Blom and Jay Weissberg assisted on the research. Thank you to the Association of Moving Image Archivists.

The Inspiration for Filibus

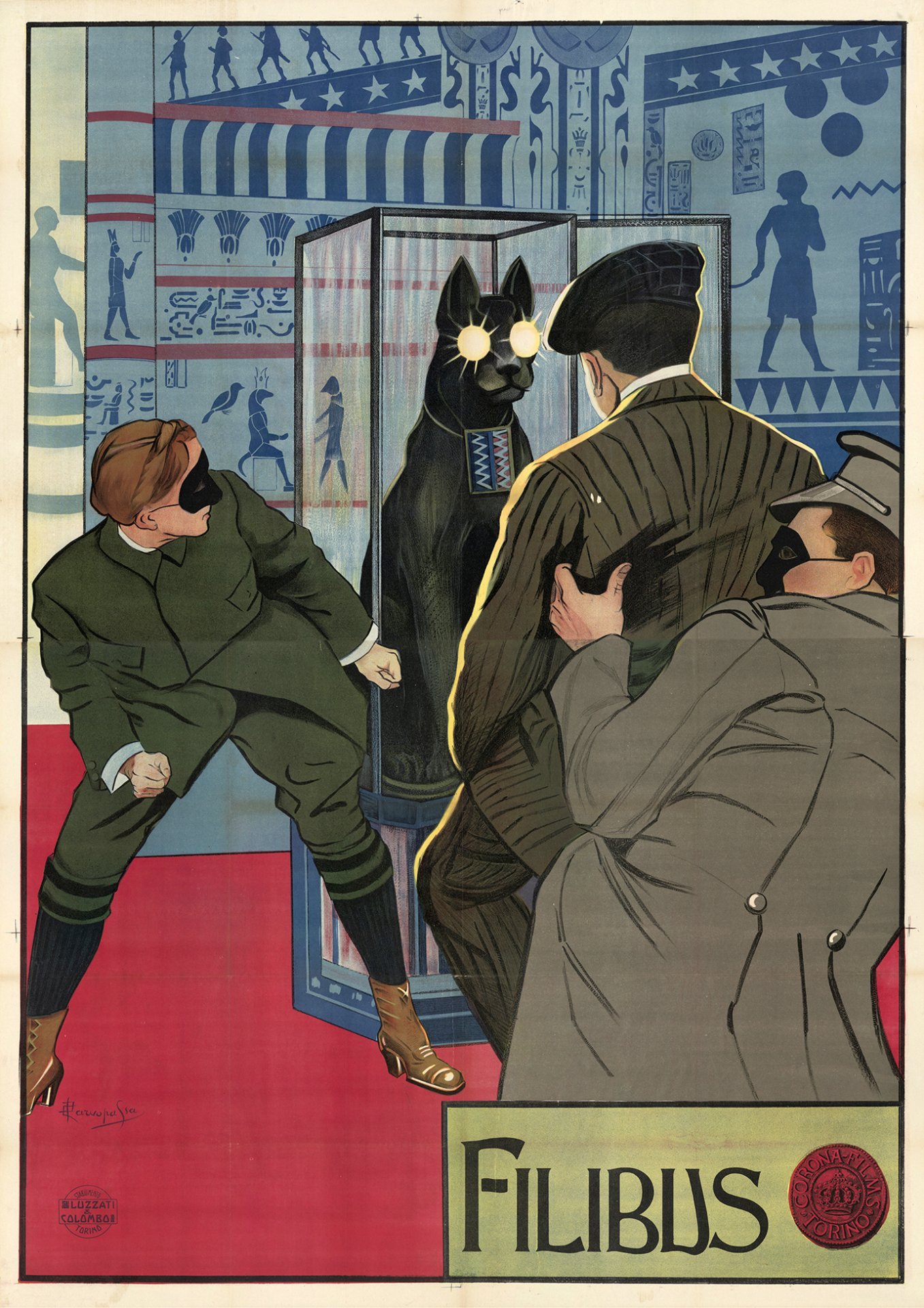

To begin with, it helps to know that the root word of “Filibus” derives from the Italian word “filibustiere”, meaning pirate or rogue.

The plot of “Filibus” comes out of the feuilleton tradition. Originally from the French word meaning a small scrap of paper, these newspaper and magazine supplements started out in 1800 as notes of local news, gossip, and criticism. The practice spread to England, where it came to mean an installment of a serial story printed in the newspaper. In fact, the original “Filibus”, was meant to be seen either as a feature or a serial in five parts. (That is the reason this restoration has retained the “Part” titles intact.)

It is also important to acknowledge the influence of Edgar Allan Poe’s character C. Auguste Dupin, who appeared in what is considered the very first detective story, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” 1841 as well as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes (“A Study in Scarlet,” 1887). The success of these fictional detectives spawned hundreds of rivals over the next 180 years. The first woman detective appeared in Andrew Forrester’s serialized “The Female Detective” (1864), featuring Mrs. Gladden as an undercover police agent. That same year, William Stephens Hayward’s serial “Lady Detective” featured the even bolder Mrs. Paschal, who “smokes, carries a revolver and discards her crinoline to go down a sewer, but also shows the sort of clinical reasoning that Sherlock Holmes would display decades later” (from www.Crimefictionlover.com). Leonard Merrick’s “Mr. Bazalgette’s Agent” in 1888 may have been the first British novel featuring a female detective. In this, fiction was far ahead of fact as the first policewoman in London was hired in 1923.

With the rise of the detective hero’s enormous popularity, there were bound to be variations on the theme and one was the master criminal. The first great “Gentleman Thief” was created by A. Conan Doyle’s brother-in-law, E. W. Hornung. A. J. Raffles and his “almost” Watson-like associate Bunny first appeared in “The Ides of March” in 1898. Raffles was such a hit that the character spawned 25 more short stories, two plays and a novel. In France, the stylish Arsène Lupin was introduced in the serialization “The Arrest of Arsène Lupin” published in the July 15, 1905 magazine “Je sais tout”. Lupin was an enormous hit for his creator Maurice Leblanc, who followed his exploits in 17 novels and 34 novellas. Raffles and Lupin inspired generations of authors including Louis Joseph Vance (“The Lone Wolf”, 1914) and Leslie Charteris (“The Saint”, 1928).

There also was a long tradition of women criminals in literature, including the most famous of all, Sherlock Holmes’ rival Irene Adler. Elizabeth Carolyn Miller writes in “Framed: The New Woman Criminal in British Culture at the Fin de Siècle” that these fictional criminals were more glamorous than the reality of impoverished women who committed petty thefts or acts of violence against their families.

From the very start, Nickelodeon owners sought to legitimize what society condemned as theaters of scandalous themes, populated by dangerous “immigrants.” Convincing women to attend would be the sign of cultural acceptance, and to entice them, filmmakers created dramas featuring the “modern woman.” These heroines were adventurous, bold, did not take a back seat to men, and, they were on both side of the law.

In 1906, actress Florence Lawrence’s first film role was in J. Stuart Blackton’s “The Automobile Thieves”, playing a criminal. In 1909, 19-year-old American director René Plaissetty (living in France) created the two-reeler “Les Aventures de Harry Wilson”, where a detective chases a beautiful woman jewel thief through St. Petersburg, Moscow and Warsaw (all shot on location), finally catching her aboard a train heading back to Paris. As the suffrage movement took hold in the 1910s, the action heroine became a popular genre. Mary Fuller, Helen Gibson, Musidora, Ruth Roland, and Pearl White were some of the most popular stars of the day.

As Monica Nolan’s fine article suggests, the creation of “Filibus” was most likely influenced by Louis Feuillade’s “Fantômas” including the opening introduction of actors and a scene where a fingerprint is re-created using a glove. However, Filibus’s joie de vivre, her good-natured battle with the authorities, her sense of humor, and her enjoyment in her stolen riches more closely aligns with Arsène Lupin.

The script’s choice of a woman thief, however, probably leads back to America and the actress Grace Cunard. It is also possible that the character of Count de Brive in “Filibus” was inspired by actress Gene Gautier’s cross-dressing “Girl Spy” series for the Kalem Company that started in 1909. Finally, it should be noted that in January 1913, Italy had its first aviatrix in the person of Rosina Ferrario — a flyer who received a fair amount of press for her daring demonstrations and exhibition flights around Italy.

One interesting note — the Parisian poet Max Jacob playfully references “Filibus” in his 1923 “Filibuth ou La Montre en or”. The poem is based on the travels of a gold watch as it changes hands, and plays with the processes of the serial novel. But the title works here as a decoy, as Filibuth never appears and the “hero” remains elusive and impossible to identify. Did Max Jacob see this Italian film? It is possible especially as his good friend André Salmon refers to this film in his poem “The Age of Humanity”: “C’est Fantômas ! C’est Filibus ! / Tous les voleurs ont des gibus.” ("It's Fantômas! It’s Filibus! / All thieves have gibus.”) A gibus is a collapsible top hat.

WHO is Filibus?

The Italian ads and poster for the film asked “Who is Filibus???” but that tagline has now taken on an ironic overtone thanks to a case of mistaken identity.

For decades, it had been assumed and asserted in many books that the role of Filibus was played by actress Cristina Ruspoli. The brilliant film scholar Vittorio Martinelli, who was responsible for identifying many early Italian films and actors, was probably the first to identify her as Filibus. Enter Ryerson University student David Emery who was interning at the EYE Filmmuseum in 2018. He was assigned, at Milestone’s request, to work on researching the history of Filibus and the little-known actress Ruspoli. He turned to the incredible resources at EYE including the legendary Desmet paper collection. Jean Desmet owned the company that originally released Filibus in the Netherlands and the care of his film and paper landed at the Dutch film archive after his death.

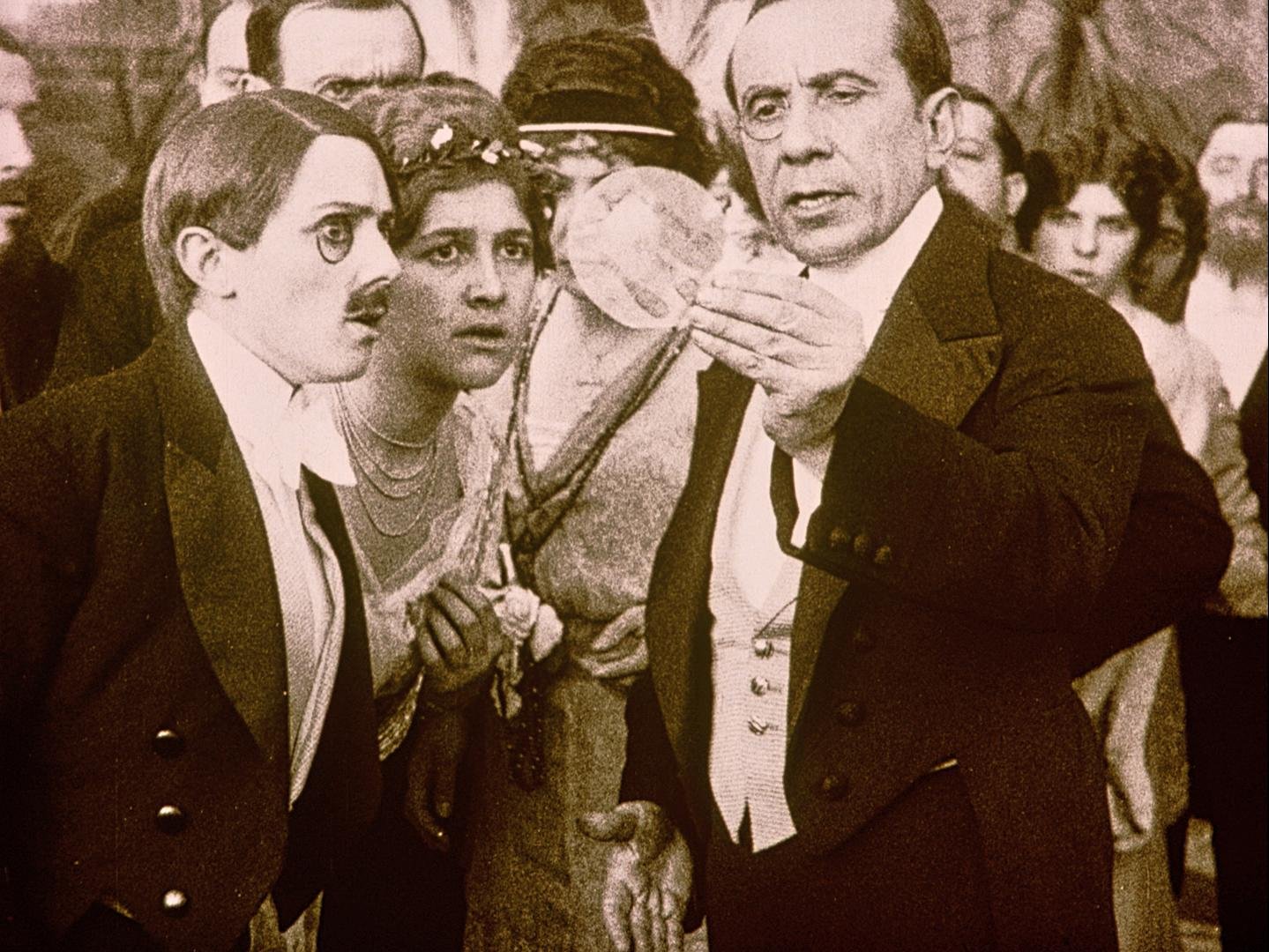

Emery went from film intern to film detective when he compared photos of Ruspoli with the film itself. First, Emery found a photo of Ruspoli from a 1913 issue of “Moving Picture News” and then compared her appearance in the 1913 epic film “The Last Days of Pompei”. Comparing those two images to our film, it became quickly obvious to Emery that Ruspoli is not the infamous Filibus, but the sister of Detective Kutt-Hendy, Léonora!

So who was Filibus!!!!

He combed through the Desmet papers with no luck. However, the Desmet collection had two other films from the production company Corona Films.

He immediately inspected them. It was in the 1916 film “Signori Giurati” (“Gentleman of the Jury”) that he made a great discovery. In a bit role of Heléne de Brian, he exposed the true Filibus! From there it was simple. In the opening credits of the Dutch print of “Signori Giurati”, like “Filibus”, there is an introduction to the actors and their roles!

Going through the Italian ads of the day, you can see that Ruspoli and Creti often appeared in “dueling” releases, so perhaps this is where the original error was made.

WHERE is Filibus?

As the history of the making of “Filibus” has been lost, the folks at Milestone and our friends around the world have made an attempt to see how and where the film was made. Jay Weisberg (programmer of Le Giornate del Cinema Muto) and his friend Violante Balbo showed the photo on the left to a friend in Genoa, who replied, “Why, that’s my house!”. The large building with the small crenulated tower, is a well-known landmark called Castello Türke, designed by late 19th-early 20th century architect Gino Coppedè. The location is Capo Santa Chiara, just east of Genoa.

Genoa is about a two-hour drive from Torino and is on the coast of the Ligurian Sea in Northeast Italy, so the scenes of Leo Sandy’s escape and landing on the beach most likely shot there as well.

There is one title card where it says that the detective has been temporarily released and back home in his villa in Abruzzo. The village of Abruzzo is (today) an eight-hour drive from Torino and Genoa and so it’s unlikely that it was used in the film.